In a mountain valley north of Kabul, the last remnants of Afghanistan’s shattered security forces have vowed to resist the Taliban in a remote region that has defied conquerors before. But any attempt to reenact that history could end in tragedy — or farce.

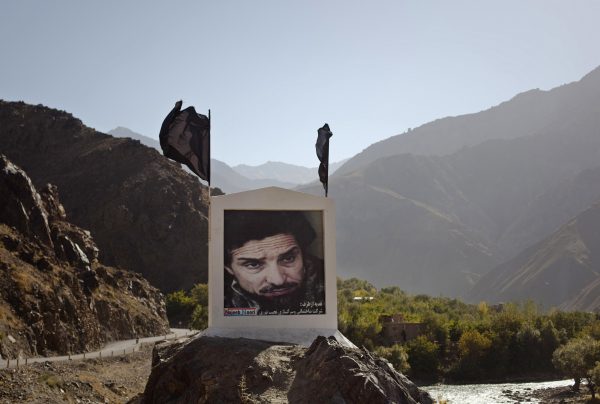

Nestled in the towering Hindu Kush, the Panjshir Valley has a single narrow entrance and is the last region not under Taliban control following their stunning blitz across Afghanistan. Local fighters held off the Soviets in the 1980s and the Taliban a decade later under the leadership of Ahmad Shah Massoud, a guerrilla fighter who attained near-mythic status before he was killed in a suicide bombing.

His 32-year-old foreign-educated son, Ahmad Massoud, and several top officials from the ousted Western-backed government have gathered in the valley. They include Vice President Amrullah Saleh, who claims to be the caretaker leader after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country.

They have vowed to resist the Taliban and are calling for Western aid to help roll them back.

“I write from the Panjshir Valley today, ready to follow in my father’s footsteps, with mujahideen fighters who are prepared to once again take on the Taliban,” Massoud wrote in an op-ed for the Washington Post. “We have stores of ammunition and arms that we have patiently collected since my father’s time, because we knew this day might come.”

But experts say a successful resistance is highly unlikely — and could potentially aggravate Afghanistan’s already considerable problems.

While the Panjshir Valley remains as impregnable as ever, it’s unclear how long its residents can hold out if the Taliban besiege the area or attack it using the U.S.-supplied armaments they have seized in recent weeks. Western countries, stunned by the collapse of a costly, two-decade attempt at remaking Afghanistan, are unlikely to invest in another proxy war.

Ahmad Shah Massoud, nicknamed the “Lion of Panjshir,” was one of the main leaders of the Afghan mujahedeen, self-styled holy warriors who defeated the Soviets in 1989. His Northern Alliance included fellow Tajiks as well as fighters from other ethnic groups, in keeping with his vision of an independent, multi-ethnic Afghanistan under a moderate form of Islamic rule.

But as the country slid into war in the early 1990s, he found himself battling rival warlords and eventually the Taliban, who seized power in 1996. During their five-year rule his forces were confined to Panjshir and other remote areas in northeastern Afghanistan.

Two days before the September 11, 2001, attacks, al-Qaida militants disguised as Arab journalists who had come to interview Massoud killed the commander in a suicide bombing.

His forces remained intact, however, and partnered with the U.S. when it invaded Afghanistan weeks later, scattering al-Qaida, which orchestrated the 9/11 attacks, and driving the Taliban from power. Along with other former warlords, they went on to form the core of the government and security forces that the U.S. and its allies would spend the next two decades arming and training, at a cost of billions of dollars.

Those forces, which from the beginning were rife with corruption, collapsed in a matter of days earlier this month, as the Taliban captured most of the country less than three weeks before the U.S. was set to withdraw its last troops.

The younger Massoud, who was just 12 when his father was killed, trained at the British military academy at Sandhurst and also earned a master’s degree in international politics from the City University of London.

He has little, if any, combat experience. Sandy Gall, a veteran foreign correspondent who wrote “Afghan Napoleon: The Life of Ahmad Shah Massoud,” described his son as “a very personable young man with political ambitions.”

Massoud says he has been joined by highly-trained Afghan special forces and other soldiers “disgusted by the surrender of their commanders,” but neither proved to be any match for the Taliban elsewhere in the country.

Torek Farhadi, an Afghan analyst and former government adviser, said the group poses little threat to the Taliban, and he cast doubt on Saleh’s claims that he could lead a resistance, calling him a “social media person.”

“If he was a real threat he should have stayed the day Ghani fled and defended the palace. He was the vice president and soldiers were under his order,” said Farhadi.

But even the specter of such a standoff, he said, risks plunging the country into another period of violence and turmoil, with dire consequences for ordinary Afghans.

The Associated Press contacted several people close to both Massoud and Saleh in order to seek comment, but was unable to reach them. Many Afghans with ties to the ousted government have fled the country or gone into hiding.

The ousted leaders holed up in Panjshir may end up joining the negotiations that the Taliban are holding with other former Afghan officials. The Taliban have said they want an “inclusive, Islamic government” but will hold off on forming one until the U.S. completes its withdrawal.

“We must use our weight with the international community to get guarantees from the Taliban for an all-encompassing government that includes women and non-Taliban,” said Farhadi.

Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, a senior Taliban official, said their forces have surrounded Panjshir. “We are doing our best to solve the issue through negotiations, but if they don’t accept the talks, we are ready to fight,” he said.

In an interview with the Al-Arabiya news network over the weekend, Massoud said he would not surrender territory but could support a broad-based government.

A resident of Panjshir reached by phone said Massoud had warned people that the Taliban might attack and said families could leave if they wished. Those who stayed would prefer a negotiated solution but are loyal to Massoud and prepared to fight if necessary, the man said on condition of anonymity because of security concerns.

“Panjshir people are used to this,” he said. “They have gone through these situations several times and they are ready for it once again.”

0 Comments