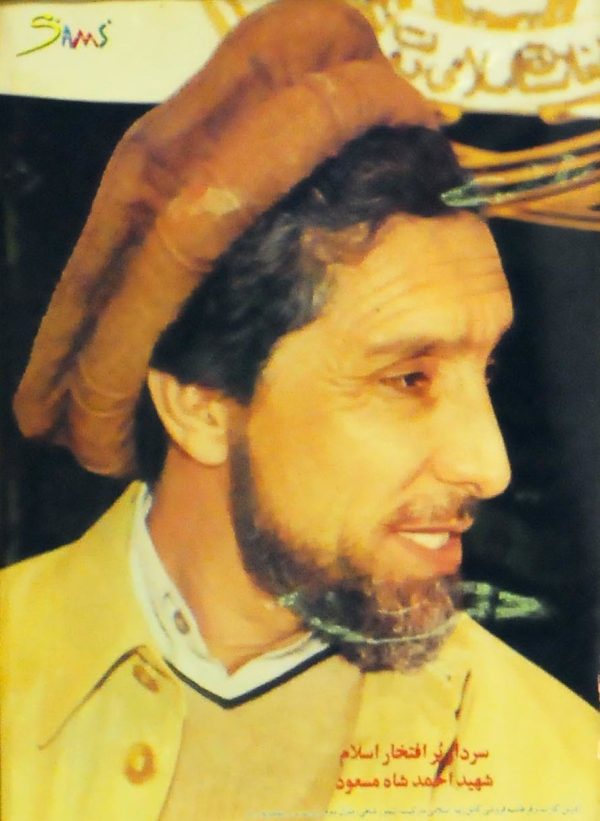

Ahmad Shah Massoud fought the Soviets from his home territory in the Panjshir Valley, and resisted the Taliban, too, until his assassination on September 9, 2001. His son, Ahmad Massoud, attempted to rally a resistance to the Taliban last month after the withdrawal of U.S. forces and shockingly quick collapse of the Afghan government; in doing so, he was tapping into the family legacy of resistance. The elder Massoud has been dead for 20 years, but his reputation as a charismatic guerrilla commander lives on — alongside questions of what could have been if he had lived.

Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979 to bolster a nascent communist government in Kabul, Western powers sought out ways to support the resistance and found the leader among the many mujahideen groups they needed in Massoud.

Sandy Gall, a renowned British journalist, embedded with Massoud during the Soviet occupation. In n a new book drawing on his years of reporting from Afghanistan and Massoud’s personal diaries, Gall details the history of the man, an “Afghan Napoleon.”

After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, why was it British intelligence (and not the Americans) that went out to meet Ahmad Shah Massoud, “this chap up in the Panjshir”?

Largely as a result of its painful experience in Vietnam, but also because of a reluctance to place its own servicemen in direct confrontation with troops of the Soviet Union, America outsourced its intelligence operations in Afghanistan and did not send its own people into Afghanistan with the mujahideen. It preferred to rely on Pakistani intelligence and its recommendations of which groups and which commanders to support.

The British and the French did not have the same constraints and sent intelligence agents and special forces people inside Afghanistan. Both countries developed strong ties with Massoud and offered him support.

While the British set out to find an “Afghan Napoleon,” what had Massoud set out to do? How did he come to lead forces against the Soviets? What motivated him to fight the Soviets and later the Taliban?

Massoud had started his own fight against the Afghan communist government in the summer of 1979 in his home region of the Panjshir Valley. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December of that year he was already building and training his forces and soon switched his focus to the new and greater threat of the Red Army, which within months mounted its first offensive against the Panjshir Valley.

His success in building resistance against the Soviets, and expanding his base of control made him one of the most prominent guerrilla commanders and resulted in his success in leading the toppling of the communist government in 1992.

His struggle against the Taliban from 1996, after the group seized Kabul, came out of the same sense of Afghan nationalism and deep religious belief. He described the Taliban as not their own masters, a movement which was supported by Pakistan according to its interests, and which distorted Islam for its own purposes.

In the book you weave together a recounting of the history with your personal recollections and experiences and passages from Massoud’s diaries. Why was it important to include Massoud’s diary entries in the narrative? What do they tell us that his achievements can’t?

Massoud’s diaries, of which I saw several volumes, offer a unique and extremely valuable insight into the course of the war in Afghanistan. In the detail of his military and political analysis, and his careful logs of the challenges of running a guerrilla war, they reveal Ahmad Shah Massoud to be both a brilliant military strategist and an able administrator. They also show a personal side, his taste for books and his love of poetry.

Massoud was assassinated two days before the 9/11 attacks. Was that a coincidence or by design? At the time, what was the reaction to Massoud’s death?

There is no doubt that his assassination two days before the attacks of 9/11 was by design. Osama bin Laden had offered to Mullah Omar to remove Massoud, who was his most significant rival and the main obstacle standing before the Taliban’s aim to conquer the whole of Afghanistan. The immediate aftermath of his death was a celebration by the Taliban and the Arab fighters allied with them in Afghanistan and together they made an attempt to seize the last parts of Afghanistan still held by his forces.

With the arrival of the Taliban in Kabul as the United States moved to complete its withdrawal from the conflict in August, Massoud’s son — Ahmad — has pledged to fight from the same valley as his father. Will there be a second Afghan Napoleon?

Certainly Ahmad Massoud has picked up the mantle of his father, announcing a new resistance movement to Taliban rule and making a powerful call for a free, democratic Afghanistan that is inclusive for all ethnicities and tribes. For now he seems to have lost ground — the Taliban have captured the main part of the Panjshir Valley, which Ahmad Shah Massoud never ceded — but I would not say that is the end of the story.

0 Comments