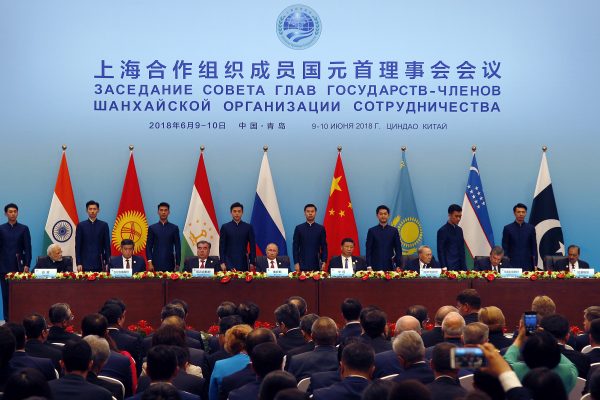

Recent remarks by Russian and Iranian officials suggest that Iran is on the verge of gaining full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a regional forum launched in 2001 by China, Russia, and the Central Asian republics (minus Turkmenistan) to combat the so-called “three evils” namely “terrorism, separatism, and extremism.” Iran has awaited this moment since becoming an observer member of the SCO in 2005. After signing a multidimensional 25-year strategic treaty with China and preparing to make a similar deal with Russia in the near term, Iran’s accession to the SCO could be seen as the third decisive move in Tehran’s deep inclination toward the East.

The Raisi Government and Iran’s New Turn to the East

Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi, has not been a leading figure in Iran’s foreign policy decision-making. That’s why, unlike his predecessor, he has not yet outlined the dimensions of his foreign policy strategy or specified what goals he wants to achieve abroad. Nevertheless, he is surrounded by individuals who were critics of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). These same voices criticized the Rouhani administration for not paying enough attention to relations with Russia and China and not using the presumably expanded ties with Moscow and Beijing as leverage in the negotiations with the United States and Europe. Though this camp has never made explicit how, exactly, the West will be impressed into lifting sanctions or accepting Iran’s other demands by Iran’s assumed close ties with Russia and China, they have gotten new credentials from the country‘s top decision-maker.

In a last short meeting with Rouhani and his cabinet, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei once again slammed Rouhani for “trusting” the West, foreshadowing a continued deadlock in the Vienna negotiations on reviving the JCPOA. Tellingly, the Supreme Leader’s office then released a short video file in which Ayatollah Khamenei, during a private meeting in 2012 with the then-head of the Expediency Council, Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani, is seen decrying Rafsanjani’s insistence on forging a relationship with the U.S.

The Supreme Leader laid out the central contour of the next phase of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy, and the direction that Raisi should pursue: displacing the JCPOA as the focal point of Iranian foreign policy. The mandate for Raisi and his team is to reinforce relations with non-Western countries, including China and Russia. On the sidelines of the endorsement ceremony of Raisi’s presidency by Ayatollah Khamenei, Ali Akbar Velayati, the Supreme Leader’s consultant in international affairs, also asserted that the priority of Raisi government must be “looking to the East” and “cooperation and strategic relations with China, India and Russia,” which could “help our economy to make progress.”

The SCO Won’t Give Iran What It Needs

The SCO is not a regional functional community in trade and economics, however. It is primarily a platform for Russia and China to manage their periphery security environment and to neutralize common threats to their national security and territorial integrity emanating from the “three evils.” Since Pakistan and India joined the SCO in 2017, the organization now includes four nuclear powers with different security agendas and goals.

Basically, Iran doesn’t share the primary concerns of these four powers. Being a full member of the SCO will be different from holding observer status; Iran will have to make commitments and take an official position during decision-making processes. As a member of the SCO, Tehran may be required to express its position toward, for instance, the territorial disputes of India with China and Pakistan – an issue in which Iran is not directly concerned. The two major economic partners of Iran, Beijing and New Delhi, will have divergent expectations of Tehran.

While full membership imposes additional obligations, it’s debatable what the benefits will be. The SCO won’t provide Iran with the capacity to pursue its Middle Eastern security agenda and concerns, nor will the body serve as an instrument for Iran to escape from regional isolation. On the contrary, gaining an SCO member tag may amplify the divisions and antagonism between Iran and the United States’ Arab allies in the Middle East by depicting Iran as a Chinese and Russian “puppet.” Although the SCO is not a collective security organization, it considers Islamic Sunni radicalism as a common threat that should be suppressed. Shiite Iran’s approach to this subject at the SCO won’t remain without sensitivities, particularly in Central Asia.

Despite other soft aspects of multilateral cooperation it claims to cover, such as trade, banking, or emergency assistance, the SCO’s history reveals a tendency to promote the common security agenda and sideline issues of disagreement. For example, because of concerns about losing its influence, Russia opposes Chinese proposals of creating free trade zone between the SCO members. Obviously, Iran can’t seek an incompatible agenda in this context.

Overall, in the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic, furthering foreign security policies already overshadows economic diplomacy or new trade opportunities. Given that context, forging institutional ties with the SCO as a full member will further strengthen such an unproductive trajectory for Iran’s economy and trade.

Even if Iran decides to grant precedence to security multilateralism over other issues, naturally, Tehran must prioritize the Middle East and the rehabilitation of broken relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council members through regional dialogue. The SCO will not help in that regard.

The turbulent Middle East and constant hostility between Iran and the U.S. and Arab countries primarily serve Russian and Chinese influence and interests. Unlike their benign (and empty) diplomatic gestures and rhetoric, Moscow and Beijing have never endeavored to substantially encourage Iran and the region to initiate an inclusive regionalism and dialogue for lasting peace and stability.

One of the main reasons for keeping Iran out of the SCO, despite its repeated requests for admission since 2005, was the Islamic Republic’s engagement with the West and Tehran’s hope for economic and political opening with the United States and Europe at different historical junctures.

Russia and China were not going to give SCO admission to a country with a West-oriented foreign policy. Full membership would give a considerable deal of leverage and a bargaining chip in the organization. It appears that the emergence of strategic deadlock between Iran and the West on the nuclear question, and Tehran’s persistence in rejecting negotiation on non-nuclear issues (for example, its regional activities and missile program), has created enough impetus for Russia and China to see “no obstacle on the way of Iran’s full membership in the Organization.”

Iran’s Misconception About Eurasian Regionalism

During the years of tensions with the U.S. and European powers, Iran has always tried to use its ties with China and Russia as leverage against the Western capitals, receiving diplomatic support, an economic lifeline, and defense equipment from Moscow and Beijing. Tehran’s strategy worked to some extent and, for example, helped it survive crippling sanctions. Still, Iran managed to not deviate sharply from its basic slogan in the foreign policy area, “neither East nor West.” However, it seems that the Islamic Republic is changing course by replacing symbolic acts with concrete policies. That, in turn, will bring a variety of repercussions for the country’s economic, foreign, and security policies.

Iran pursues meaningful participation in Eurasian economic and security institutions with the hope to decrease the pressure of Western sanctions and probably to make new scenes for a “diplomatic showoff” against the West. Nonetheless, this mindset lacks a specific strategy and coherent policy and sometimes contradicts Iran’s foreign policy discourse, which prioritizes the Middle East and developing relations with neighbors.

There is a misconception in Iran’s foreign policy that merely being a part of the different regional bodies in neighborhood regions, including Eurasia, could spontaneously break the “sanctions wall” and lead to diversified fruitful foreign relations. It is hard to imagine any real, meaningful accomplishments will result from multilateral platforms such as the SCO, Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), rather than Iran’s bilateral relations with Russia and China. Instead, Iran’s insistence on having a seat at the table only generates more leverage for Moscow and Beijing to bolster the country’s overreliance on the East.

Efforts to gain a seat in these largely ineffective initiatives, where Russia and China are the dominant stakeholders and it is nearly impossible for Tehran to seek tangible and achievable goals, does nothing but waste the limited diplomatic resources of the country. In terms of trade and economics, which matter the most to Iran, Eurasian great initiatives like the Russian-led EAEU and China’s BRI haven’t even brought about even significant developments in Beijing-Moscow bilateral relations or even regional institutional coordination of the two initiatives, despite lip service in that regard.

The BRI and EAEU are geopolitical projects to protect China and Russia’s “spheres of influence” under the banner of a multipolar world order. Due to Iran’s regional and international entanglements, opportunistic Russia and China, with their global ambitions, will cultivate certain affinity with Iran, regardless of Tehran’s presence in the multilateral forums.

0 Comments