Much has been written about the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), one of the six limbs of China’s Silk Road Economic Belt. Supporters hail CPEC as equipping Pakistan with the infrastructure to thrive in the 21st century, while critics deem it as a form of colonization that will doom Islamabad into being a vassal of Beijing. As CPEC recently concluded its early harvest period in 2021, it’s a good time to evaluate the impact it has had on China-Pakistan trade patterns.

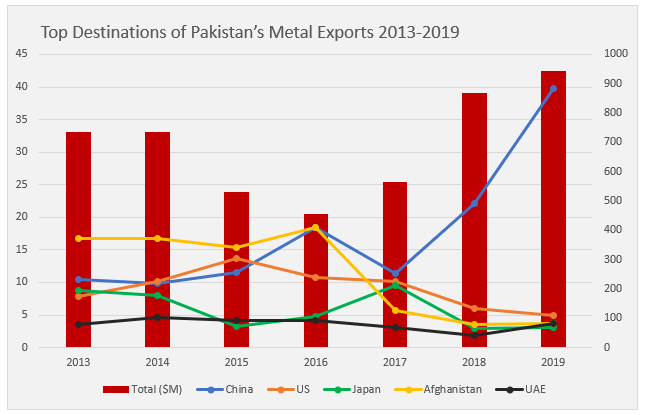

One profound change that would add to the debate is the unprecedented spike in metal exports from Pakistan to China since 2016, the year CPEC officially began. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, prior to CPEC’s unveiling, the top shares of Pakistan’s metal exports were split among Afghanistan, China, Japan, the United States, and the UAE. However, after two consecutive dips in 2015 and 2016, exports have increased steadily since 2017, with most of the gains going to Beijing. As a result, China now receives far more of Pakistan’s metal exports than its previously close competitors.

Source: Author’s compilation based on data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity

This spike is attributable to China’s intense investment into Pakistan via CPEC. Indeed, the $64 billion project has significantly improved Pakistan’s connectivity and energy production and has reanimated the country’s mining sector, which had suffered from high transport costs, low investment, and inadequate infrastructure.

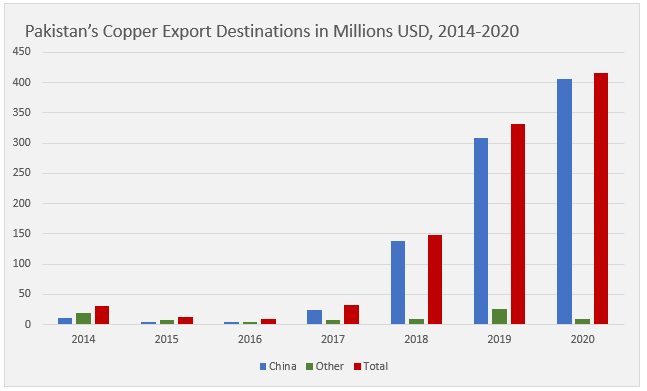

Among the metals more intensely pulled in by Beijing’s new magnetism is copper. In 2014 Pakistan exported under $50 million in cooper to China; in 2020, that figure topped $410 million.

In addition, this development has seen Pakistan turn from a net importer of refined copper to a net exporter as of 2018, a feat not accomplished since the year 2000. For China, this new stream of copper, despite constituting under 3 percent of total copper imports, addresses internal concerns over the environmental damage caused by local copper production. By outsourcing the production of copper, China can maintain the supply required to satisfy growing demand for its green technology products such as solar panels and electric cars, in which copper is an integral element.

Author’s compilation based on data from UN Comtrade.

For CPEC proponents, the export surge joins the list of benefits accrued from partnering with Pakistan’s “iron brother” and all-weather friend. However, this new source of revenue has not been painless. Protests erupted at Saindak Copper and Gold Project with workers demanding an increase to their salary of 15,000 Pakistani rupees, a sum whose value further diminished as rising inflation pulled the value in U.S. dollars down from $106.5 in January 2019 to around $95 in August of that year. The Saindak project is a joint Beijing-Islamabad venture located in Pakistan’s restive Balochistan region, where local opposition to China’s development has at times turned violent. Moreover, loan repayments and their accruing interest will not see Islamabad basking in the new wealth CPEC may generate; instead Pakistan will be scrambling to repay debt to China, which has become greater that the money owed to the IMF.

Geographic proximity is certainly an important factor diminishing transport costs prior to export. Given China’s shared border with Pakistan, domestic pollution problem frequently lamented in public discourse, and burgeoning green technology sector, market physics dictate that cheaper and more abundant copper in Pakistan would naturally channel eastward. Another factor, however, is the growing complementarity between Pakistan and China.

This increased production and export of Pakistani metals, a raw material, to a more developed and richer state feeds into discourse on the effects of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), particularly on what it means for the hegemony of the United States. Indeed, those cynical about the fortitude of U.S. hegemony would see the above copper surge as indicative of China’s hegemonic gains. This is because a classical facet of the relationship between a hegemon and its subordinate peripheries is (relatively) cheap raw material and labor moving from periphery to core, while (relatively) expensive products and expertise are exported in the opposite direction.

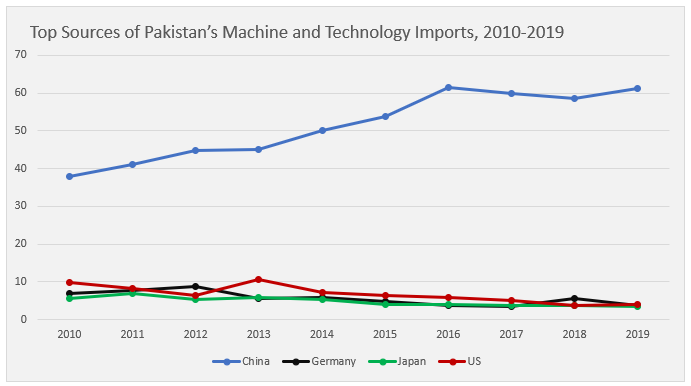

Intriguingly, taking machines and electronics as examples of China’s pricier exports to Pakistan, one sees that while China’s supply to Pakistan has long dwarfed exports from the United States and Japan, this gap increased in the years prior to CPEC’s start in 2016, after which China’s share plateaued at roughly 60 percent of total imports.

Source: Author’s compilation based on Pakistan Mach and Elec Imports by Country & Region 2019 | WITS Data, n.d.)

For world-systems analysts observing the different manifestations of hegemony since its first incarnation as the United Provinces of British India, these developments resonate with the peripheralization of areas once external to the hegemon, whereby its economic outputs become more in tune with the hegemon’s orchestration of supply and demand. In this vein, a periphery is molded by the hegemon into a producer of cheap goods and labor that it requires for its more expensive products and exports, in so doing engineering the classical asymmetry between hegemon and periphery. This asymmetry is one of revenue, if nothing else, structured in such a way as to guarantee that net revenue enters the hegemon from the periphery, with a trade imbalance and the abovementioned interest payments inflating China’s gains.

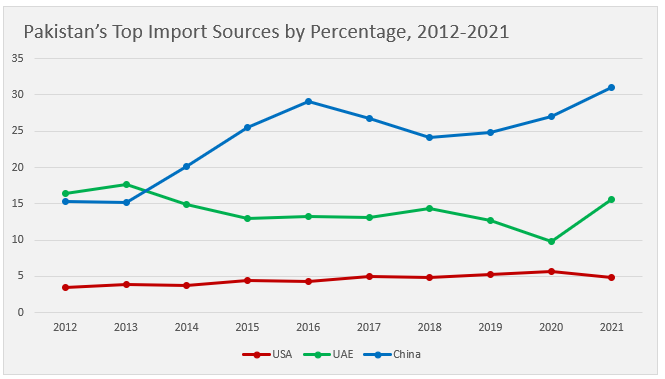

In this regard, a glance at Pakistan’s top import sources reveals China’s share has doubled since 2012 – going from 15 percent to over 30 percent – while rivals such as the UAE and the U.S. remained at roughly their pre-BRI levels.

Compiled by author based on data from: Pakistan | Imports and Exports | World | ALL COMMODITIES | Netweight (Kg); Quantity and Value (US$) | 2009 – 2020, 2021.

What does this mean for U.S. hegemony? Some Pakistani scholars say China has already achieved hegemony in Pakistan, with these latest trade victories being only parts of an apparatus of control, including cheap imports corroding local manufacturing and leading to deindustrialization.

Multipolarity, or a world with two or more hegemons, has accompanied analyses of similar gains China has made at the expense of the United States and the international liberal order, especially as China’s imprints on developing states become more glaring. An increasing number of states are joining China’s international institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and more are adopting the One China position at the government and United Nations levels. China has also become a top destination for students from developing countries, with this educational migration eastward involving education on Chinese language and culture in a manner set to groom returning students into a Mandarin-speaking counterweight to Western-educated elites at home. In Pakistan, China has even achieved the level of trust once given to Washington in security affairs, as Islamabad has rejected a recent request to host a U.S. military base to monitor Afghanistan while the People’s Liberation Army traverses contested territory in Kashmir.

China’s economic gains in Pakistan have not been met with much alarm, compared to the all-out attempt to stop Vladimir Putin from conquering Ukraine. This is a quiet skirmish, one that plays out in markets and factories, declared with free trade agreements and fought with efficient products. This war is more silent than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but just as capable of furthering Beijing’s influence. Through comprehensive design and sustained perseverance, China can extract from Pakistan all the benefits of a periphery that are the stuff of Putin’s fantasies in Ukraine.

Indeed, Putin may be teaching Xi Jinping a valuable lesson: Enduring and organic influence over other states must be pillared by economic promise. In poetic justice, Moscow’s use of force in lieu of Western economic allure (and cultural appeal) has pulled it farther than ever from great power status as sanction after sanction whittle away at an economy Putin’s apologists would have used to defend his heavy-handedness domestically and in Moscow’s satellites.

How CPEC Has Altered China-Pakistan Trade

Source: Frappler

0 Comments