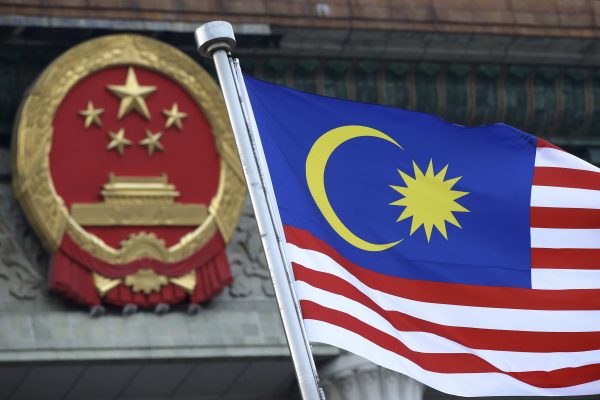

When a threat grows more imminent, conventional belief holds that a state would respond by increasing its capacity to counter, deter, or deny that threat. But as China’s grey zone activities in disputed parts of the South China Sea have increased since 2013, the Malaysian government has not fundamentally changed its defense posture or its policy of non-alignment to defend itself against the threat posed by China’s actions.

At least since 2013, Malaysia has experienced numerous incursions by China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels into the contested waters off the coast of Sabah and Sarawak, which Kuala Lumpur has described as a form of “white hull diplomacy.” The People’s Liberation Army Navy and Air Force have also occasionally crossed into Malaysia’s maritime zone. Indeed, since 2013, this “white hull diplomacy” has become nearly permanent.

Yet the dominant view in Malaysia holds that China does not pose a threat, and that these Chinese incursions do not constitute a violation of the country’s sovereignty. As a result, they are insufficient to prompt a revision of Kuala Lumpur’s regional outlook.

In March 2019, then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad noted that “at the moment we [Malaysia] have not found them [China] a threat to our security. Not yet, maybe later.” At the crux of Mahathir’s statement was a constructivist threat perception: the idea that Beijing is a threat if you make it one. This sentiment was echoed during many of the closed-door roundtables I attended in Kuala Lumpur between July and November of 2022. The Malaysian elites could easily join the bandwagon in demonizing Beijing but have continued insisting when talking to their Western counterparts that they were not concerned about China, while simultaneously encouraging a Western presence in Malaysian waters.

Instead, to generate a sense of security, Kuala Lumpur is convinced that the most effective defense strategy is to make its relationship with Beijing indispensable.

How do we make sense of Malaysia’s insistence that China does not pose a threat?

Like its neighbors, Indonesia and Singapore, Malaysia is a hedger that desires the United States to contribute to regional stability and China to contribute to regional prosperity. However, Malaysia’s means of hedging incorporates a set of unique beliefs that has made it much more cautious about jeopardizing its relationship with Beijing.

First, Malaysia’s constructivist threat perception of China is underpinned by an assumption that labeling is a self-fulfilling act. As noted by the Malaysian scholar Cheng-Chwee Kuik, this view can be traced back to Mahathir’s statement in 1997: “Why should we fear China? If you identify a country as your future enemy, it becomes your present enemy – because then they will identify you as an enemy, and there will be tension.”

In contrast to other regional navies such as those of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, which have tended to confront CCG incursions into their claimed waters, Kuala Lumpur has taken pains to explain that such incursions should not be a source of concern. During the roundtables I participated in, Malaysian elites often defended their relationship with China as cordial and a source of security. Moreover, Kuala Lumpur draws a distinction between the “white hull” and PLA Navy (“grey hull”) incursions, noting that incursions by CCG ships are tolerable because their jurisdiction is based on land; thus, their mere presence in Malaysia’s maritime jurisdiction does not constitute an assertion (or violation) of sovereignty. This was consistent with Kuik’s finding, drawn from a conversation with a veteran diplomat, that not viewing China as a threat was a “deliberate policy.”

Malaysia’s downplaying of assertive Chinese actions is shaped by a theory of action-reaction spiral, which posits that careless acts of provocation have the potential to drag Malaysia into a cycle of crises. Malaysia’s reaction to major power calibration in the region, such as last year’s creation of the AUKUS pact, has demonstrated its constructivist belief that aggression begets aggression, provoking arms competition in the region. As Malaysian scholar JN Mak has observed, the no-threat assertion is also crucial in enabling Malaysia to build its defense capability based on what is most affordable instead of tailoring it to a specific threat.

During the roundtables, Malaysian elites often criticized the zero-sum mindset embodied in U.S. defense documents, such as its 2022 National Defense Strategy, which singled out China as a threat. Even as they continue to express their tacit support during personal engagement with the U.S. presence in the region, this often comes with a warning that singling out China as a threat is destabilizing.

This criticism highlights the second crucial point, about how threats are conceptualized in the minds of Malaysian policymakers: The country’s tendency is to ascribe a threat not to an actor but to an action. In this respect, some Navy officers compared the U.S. National Defense Strategy to Malaysia’s 2019 Defense White Paper, which does not single out any countries as posing a threat.

The third element is the most distinctive feature of how Malaysia evaluates threats: Kuala Lumpur calculates threats in relational terms.

In sum, Malaysia tends to distinguish tactical threats, or the general day-to-day insecurity of dealing with China’s grey zone activities in its waters, from threats that would affect its core national interests with China, which center around deepening the two countries’ economic relationship. Because the tactical threat falls short of threatening Malaysia’s national interests with China, as long as Kuala Lumpur views Beijing as respecting its core limits, it is comfortable in tolerating acts others have found hostile, such as incursions into one’s maritime zone or airspace.

Malaysia started to embrace a relational calculation after it incorporated the idea of China as a staying power, as opposed to others that are transient. With a powerful China deemed as a constant in Malaysian foreign policy, the country needs an outlook that allows it to manage the relationship over the long term.

The process of acceptance started as Malaysia reassessed its relationship with the West in the 1980s, when it saw evidence that the United States could not be expected to cater to Kuala Lumpur’s regime security needs or to align with Kuala Lumpur’s vision of regional security. The evidence ranged from protectionist measures that hurt Malaysia’s economy to the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam and unwillingness to play a larger role in Cambodia. These forced Malaysia to diversify its relationships, including with China, a country that Mahathir in 1984 said he wanted to keep “at arm’s length.”

At the time, the way Malaysia calculated the China threat placed much emphasis on its allegedly expansionist national character. For example, in July 1984, Mahathir warned U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz not to arm Beijing to help it wage war against the Soviet Union because, as Mahathir put it, “a prosperous China, a more economically advanced China, would be equally a militarily strong China, which could then revert to the policies of hegemony, which from a historical perspective in this part of the world has always been found to be a serious concern.”

The predisposition-based evaluation changed gradually as both countries deepened their relationship in the post-Cold War period. Assessing threat from a relational perspective makes Kuala Lumpur’s concept of redlines vis-à-vis China pliable: Hostile actions could be explained away as one-time acts. Even if these repeatedly occur, as long as both sides have open channels of communication, find ways to manage the tension, and understand each other’s point of view, then things need not be blown out of proportion. During one roundtable in November, Royal Navy officers said that they have had direct contact with Beijing during recent incidents in the South China Sea, which mitigated the fear of the Chinese incursions.

One fine line is to distinguish relational assessment from bandwagoning for profit or a claim that Malaysia is already bought by Chinese money. The role of corruption, such as during former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s administration, cannot be discounted and, in fact, has been crucial in enabling China to push the boundaries of what is acceptable. But it is insufficient to explain why Malaysia started dispelling the China threat view while both were economic competitors in the late 1980s and early 1990s, or why Kuala Lumpur has continued to avoid escalation across administrations.

Mahathir won an election in 2018 by demonizing Najib’s partly Chinese-sponsored corruption, but once in office, remained restrained in his rhetoric vis-à-vis China. Mahathir’s subsequent predecessors, who were rather indifferent to China, also continued to evaluate the threat with a relational outlook, tolerating tactical concerns as long as both countries’ relationship was otherwise viewed as close.

It is crucial to see the three sources of Malaysia’s constructivist threat perception of China as dynamic yet stable ingredients in how Kuala Lumpur has formulated its policy toward a newly powerful China. To be sure, this may change if the mantra of Beijing as a staying power is debunked or no longer accepted as the truth, just as Malaysian views of Britain shifted after it withdrew its troops from “east of Suez” in 1971. Fundamentally, the three sources demonstrate how Malaysia generates a sense of security in an insecure region by leveraging its relationship with a nearly risen power.

Why Don’t Malaysian Policymakers View China as a Threat?

Source: Frappler

0 Comments