Six years since the first Aurat March, the idea of women marching, claiming public spaces, and fighting for their rights as they take to the streets in various cities of the countries still faces severe backlash in Pakistan.

This year was no different.

The theme of the 2023 march in Islamabad was “Feminization of Climate Justice,” which aimed to describe climate justice from a feminist lens.

On the day of the march, which was held on International Women’s Day (March 8), participants and organizers were baton-charged by the police. Barbed wire was placed along the road leading to the venue and for hours the march was not allowed to proceed as containers were placed on the route.

Organizers of Aurat March Islamabad applied for a No-Objection Certificate (NOC) on January 6, two months before the march, and met with the district administration twice regarding the matter but received no substantial response.

“On the day of march, two police officers came to us and told us there are security issues. We said we were already clear that we won’t negotiate. We knew that the police were trying to waste our time,” Huda Bhurgri, organizer of Aurat March Islamabad, told The Diplomat.

“We knew that the state was hijacked by the religious fundamentalists who carry their so-called Haya March (Modesty March) and are issued NOC. The entire Faisal Avenue was open for Haya March, but we were cordoned off. For us there were barriers, barbed wire, and we were isolated,” she added.

She added that the police tried to push participants away and warned the organizers that arrests could take place.

“If they were concerned about security, they should have spoken to the Haya March participants who had sticks with them while we had nothing except our placards,” said Bhurgri.

Shipping containers were used to stop the marchers from marching toward D-chowk, but after hours of resistance the march happened. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Regardless of all the barriers and challenges, the organizers and participants resisted for hours until the shipping containers were removed, and the Aurat March Islamabad commenced.

In Islamabad, hundreds of participants marched, carrying placards and slogans highlighting the various issues that women in Pakistan face. The country ranks second worst on the World Economic Forum’s 2022 Global Gender Gap Index, trailing only Taliban-ruled Afghanistan.

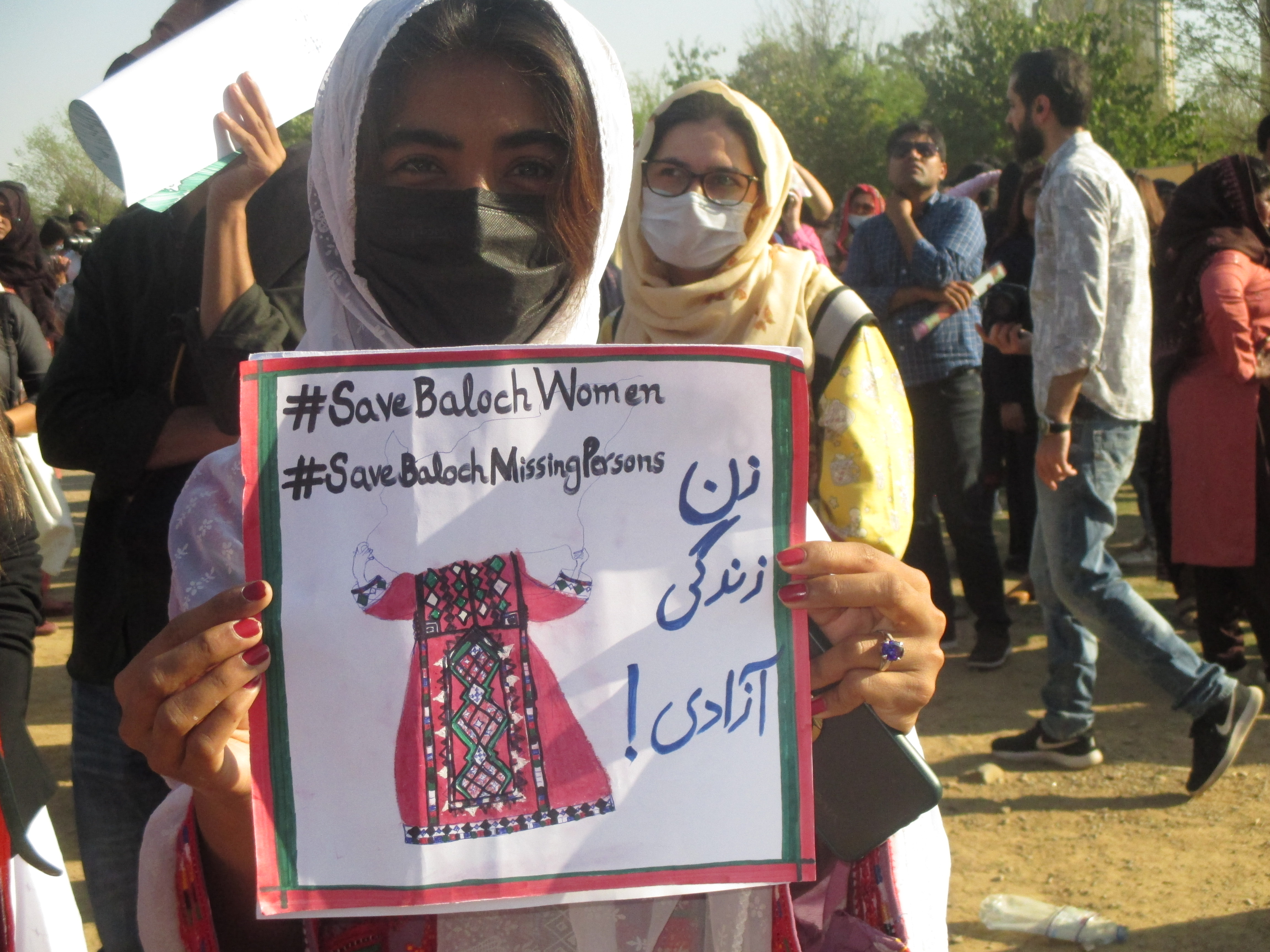

Hira, a politics student at Quaid-e-Azam university, participated in a “march for Baloch women and against enforced disappearances.”

Hira, a politics student at Quaid-e-Azam University from Balochistan, said she was marching for Baloch women fighting against enforced disappearances. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Nimra, a documentation staff member at Defense of Human Rights, said, “I am here to raise my voice for the rights of the women of those women who bear the brunt of enforced disappearances.”

Nimra, right, and Amna at Aurat March Islamabad. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Anmol and Arooj, who belong to the ostracized Khwaja Sira (transgender) community said they were here to march for their rights.

Anmol and Arooj from the Khwaja Sira Community said they took part in the march to protest for their rights. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Syeda Mujeeba Batool said she celebrates her birthday every year by attending the march, and that she marches for dismantling patriarchy, which is “root cause of oppression faced by women.”

Syeda Mujeeba Batool, who said she celebrated her birthday by taking part in the Aurat March. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

In Lahore, too, the organizers were denied an NOC.

“This year we sent our application earlier, during the first week of February, so that we are not called at the last minute. We didn’t hear anything from the administration and met with the District Administration (DC) who said we could march without a written NOC and that we would be provided with security,” said Leena Ghani, a volunteer at Aurat March Lahore.

“However, a few days later we received a rejection letter from the DC stating that we cannot march because of Haya March and security concerns.” The case was taken to the court, where the judgment came in AM Lahore’s favor.

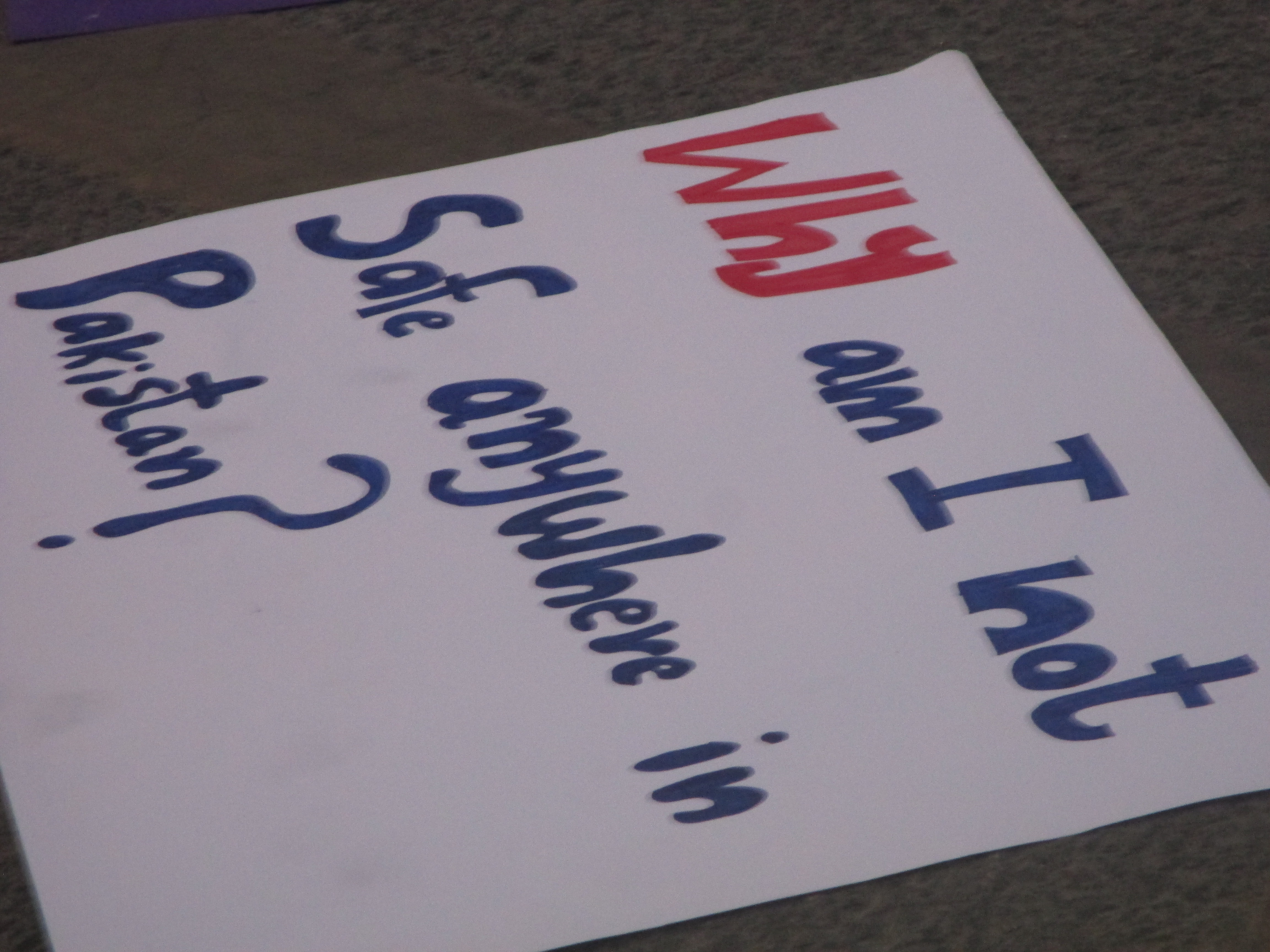

“This happens every year, but we do hope that it doesn’t because if others are allowed to march then why not us?” said Ghani.

She added, “For the first time, I would say the police were cooperative. That has not always been the case and was not the uniform experience across chapters, keeping in mind what happened in Islamabad this year.

“The only issue we had [in Lahore] this time around was the YouTubers came out in large [numbers] to disrupt the march, but our allies, volunteers, and police were able to make sure that they did not do any harm.”

The Aurat March was simultaneously held in Hyderabad, a city in Sindh province as well as Multan, in northern Punjab province.

In Karachi, the Aurat March took place on March 12, a Sunday, in order to encourage the participation of working-class women.

“Without women the revolution is incomplete,” reads a banner at the Aurat Azadi Jalsa, organized by AAM on March 5, 2023. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Aurat March and the Aurat Azadi March

Before last year, the march was organized in Islamabad by Aurat Azadi March (AAM), which differs ideologically from Aurat March in its alignment with the left. Many of AAM’s organizers are members of the Women Democratic Front (WDF), an independent socialist-feminist organization. While AM has kept itself apolitical, AAM had political affiliations with the Awami Workers Party (AWP), a socialist political party.

As Tooba Syed, who was one of the organizers of Aurat Azadi March from 2018 to 2021, told The Diplomat, “International Women’s Day has a socialist history so leftist parties have been commemorating it always. In 2018, it became bigger. Aurat March Lahore and Aurat March Karachi are non-partisans, but we believed that as many political parties aligned themselves with the movement, it would strengthen it further.”

Syed added that another difference is that AAM was not only marching for rights or women’s empowerment but women’s emancipation – which means the dismantling of the structures that oppress women, especially working-class women, on various levels.

“We do not only talk about patriarchy,” she said. “We are a class-based movement. We talk first and foremost about women from the working class because they are suppressed the most. It cannot be possible that upper-class or middle-class women share similar interests or issues as the working-class women.”

The AAM chapter was met with a lot of backlash. Things turned violent during the 2020 edition of the march, when the right wing attacked the participants by throwing stones at them.

In 2021, AAM organized the march once again, but afterwards there were many cases registered against the organizers, declaring them to be anti-religion. As per Syed, the evidence used against the organizers was clearly doctored and part of an organized campaign.

“We were highly attacked because of our affiliation with the left. We believe not only the right wing, but the state too was involved because we reached out to everyone, wrote open letters to the prime minister but to no avail. A lot of our comrades lost their jobs,” said Syed.

As the organizers of AAM started to reflect and analyze, they felt that the March was no longer serving its intended purpose. Women who had joined them from katchi abadis (urban slum settlements) could no longer take part because they started facing violence at home due to their participation.

“Women from the working class with whom we work year-long are the ones who would participate in our marches, but they were no longer able to join because of the propaganda surrounding the march, which caused problems for them at their homes,” Syed said. “That shook us because we realized that it is easy for us to leave our homes for the march but many of the women we are fighting for cannot.”

According to Syed, if AAM had carried on with the march in 2022, the organizers would have been making a conscious decision to go ahead without the participation of the working-class women who needed to be at the forefront of the movement. So, instead of going ahead with the march, in 2022, AAM, in affiliation with WDF, decided to do a jalsa (a gathering) in F-9 Park.

In 2023, AAM once again organized the Aurat Azadi Jalsa in F-9 park on the same side of the park where a woman was raped a month ago. The gathering was meant to honor her and her resistance in fighting her assailant.

The Aurat Azadi Jalsa arranged by Aurat Azadi March and Women Democratic Front. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Bhurgri, who was also an ex-organizer of AAM, believes that the decision to not march came more from WDF and AWP than AAM. This resulted in an ideological split and in February of last year a new group emerged: the Aurat March Islamabad, which organized this year’s march.

Bhurgri argues that the decision to not march came from AWP, which decided that women should not face off against the mullahs (religious fundamentalists). AWP worried that after engaging in direct confrontation with religious leaders – an important part of Pakistani society – the party wouldn’t be able to connect with the masses.

“I believe this is a very lousy explanation. When it comes to women and religious hegemony and fundamentalism, this is the stance the left has taken for long,” added Bhurgri.

She continued: “Religious fundamentalists mobilize against the Aurat March everywhere and make it an issue of morality. They call all women who participate in the Aurat March immoral. Surrendering the march in front of religious fundamentalists defeats the purpose.

“A true resistance is when all patriarchal alliances are challenged, which include capitalism, feudalism, imperialism, and at the same time religious fundamentalism. Patriarchy operates through its alliances and religious fundamentalism is one alliance.”

A poster at Aurat March Islamabad. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

What Has the Aurat March Achieved?

In the book “Contradictions and Ambiguities of Feminism in Pakistan: Exploring the Fourth Wave,” the late Dr Rubina Saigol, a Pakistani feminist scholar, identified the Aurat March as the fourth wave of feminism in Pakistan. She wrote that the various Aurat Marches are different from previous feminist waves in that the new feminists challenged the private sphere of life where patriarchy is dominant. Saigol argued that the current wave of feminism “marked a tectonic shift in the feminist landscape in Pakistan.”

Dr. Afiya Shehrbano Zia, a feminist researcher and author of “Faith and Feminism in Pakistan,” explained that the previous waves in the 1950s and 1990s were focused on fighting for basic democratic rights and challenging oppressive structures.

“Prior waves dealt with sex crimes and adultery laws, etc. but within the victim narrative – they evaded the issue of sexual freedoms in the Islamic Republic because such rights require challenging Islamic morality and legality. Just rescuing women from being framed by zina/adultery cases was time consuming and there were far fewer feminist activists or lawyers then,” Zia told The Diplomat via email.

“Firstly, the AM protests jolted, quite rudely, the tradition of sedate cake-cutting celebrations observed by women’s NGOs for decades. Secondly, this new wave unapologetically puts sexual autonomy and bodily rights at the center of their campaign – mera jism, meri marzi (My body, my choice),” said Zia.

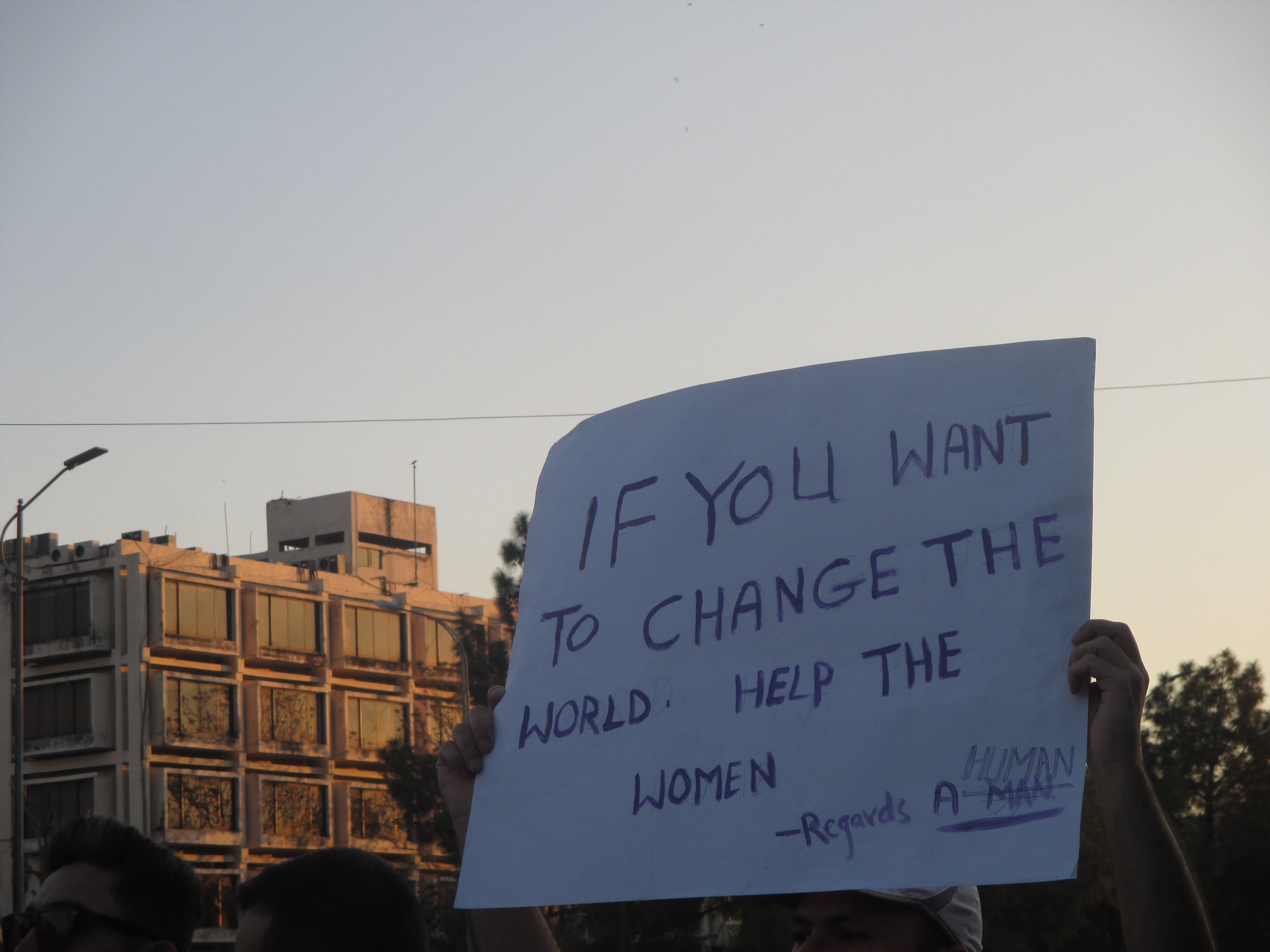

Ghani believes that AM is fighting for safe spaces and is a community. “Whenever women come out on the street – angry women, or women with a purpose or women who know what they want and women who are brave – this also includes the Khwaja Sira community and religious minorities or people from marginalized communities, they all find Aurat March to be a place where they feel protected,” she said. “AM is a community, and we want there to be more communities that prioritize care.”

A poster at the Aurat March Islamabad. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

Organizers also note that the Aurat Marches aim to function as a pressure group, whose task is to criticize state policies and give a critical analysis of important social issues. They reject as unrealistic the expectations that the movement must cooperate in coming up with solutions to women’s problems in Pakistan.

“We are not the state – we do not have the power to make rules and regulations and neither does the state engage with us. We present our demands and policies to the state and its representatives every time. It is the responsibility of the state to engage with us,” said Bhurgri.

For years, the Aurat Marches have been criticized for lack of inclusivity, but these feminist collectives have been making efforts to become more inclusive over years. However, Syed believes that since there is no one kind of feminist or one kind of woman, there cannot be one march as such to represent every woman in the country.

“In Pakistan it is not only women who are oppressed. Where she is from, which class she belongs to, which ethnicity she belongs to – that matters and determines the extent of oppression. So, Pakistan needs many kinds of feminism and not just one Aurat March is enough for it,” Syed argued, stating that if any group does not feel included, they should be able to conduct their own marches for representation.

A participant at the Aurat March Islamabad holds a poster protesting against forced conversions of minority girls. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

The Baloch Aurat March

To that end, it’s fitting that this year in Karachi and Quetta, Baloch women, who have been leading a movement against enforced disappearances for years, took to the streets for their own march on March 8.

“Baloch women face dual oppression, both from society and the state. Aurat March has focused on social issues faced by women from harassment to domestic violence. These issues are faced by Baloch women too; however, what sets apart Baloch women’s struggle is that above all the Baloch women face oppression by the state as their brothers, fathers, and sons have disappeared,” Sammi Deen Baloch, a missing persons activist, told The Diplomat. She is the daughter of Deen Muhammad Baloch, who has been missing for 14 years.

“Although Baloch women are always on the road and protesting outside press clubs, we felt that even on International Women’s Day we should organize a march on this occasion to carry on our movement against enforced disappearances so the plight of Baloch women can end insofar as this issue is concerned,” she continued.

Sammi added that Aurat March Karachi, for the last couple of years, had been inviting her and giving the issues faced by Baloch women a space where they could briefly put forth their struggle. AM Karachi organizers also participated in the march organized by Baloch women.

However, Sammi said that other than this, she hasn’t seen a response by feminists on Baloch women’s issues that is worth mentioning or appreciating.

A poster at Aurat March Islamabad. Photo by Somaiyah Hafeez.

The Way Forward

Many believe that for it to become a movement in the true sense of the term, the Aurat March needs to move beyond an annual event, graduating into a continuous struggle for social change.

Could this be done perhaps by the centralization of the Aurat March, with different chapters coming together as one? Syed thinks not.

“I think Aurat March should remain autonomous and expand and evolve. You cannot learn by doing the same thing again and again. We can try different things and then share our experiences,” she said. Syed added that while the marches have been taking place for years, no meaningful dialogue has taken place between the organizers of different chapters.

Dr. Nida Kirmani, a sociologist, thinks that the “more dispersed, decentralized model” of the Aurat March, with different groups taking out their own marches in different cities, can be viewed both as a strength and a weakness. “It allows for more diversity in terms of voices and approaches, but it also means efforts are dispersed rather than focused in one direction,” she said.

“The debate of whether these annual events are just performances or movements remains unresolved,” said Zia. “Yes, some members work on issues with other collectives all year around, but not as AM. No cases are fought, no lobbying with the state or government and no roadmap to forming an autonomous political entity.

“Each year the state and Right are managing to dilute and chip away its radical potential. So what its worth going to be in the future? A rethink is imperative.”

“The whole country now knows about Aurat March — it has shaken the structures, but how does it become a movement of the masses from the movement of urban, educated women along with working-class women and allies?” said Syed. “I think that’s the next step to go beyond a one-day event.”

Pakistan’s Aurat March 2023: Another Year, Similar Challenges

Source: Frappler

0 Comments