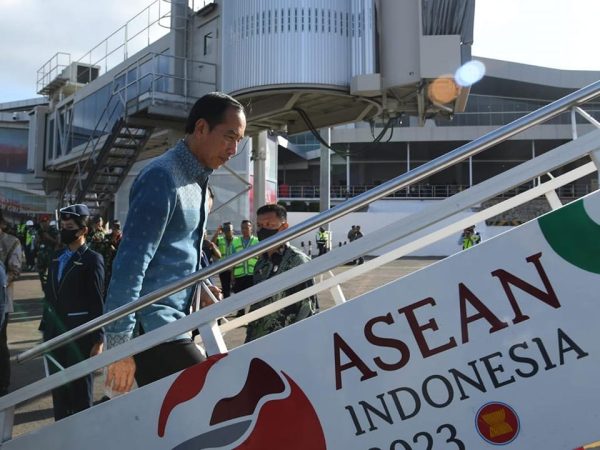

There should be no surprise that the summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), hosted by Indonesia last week, was branded with the slogan “Epicentrum of Growth.” President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo is well known for his focus on infrastructure and living standards and he views ASEAN first and foremost as a forum for trade and investment.

This economy-centric approach has proved popular at home, winning Jokowi reelection in 2019, while his high popularity ratings today reflect Indonesia’s continued strong growth in the face of a global recession. Indeed, with most of the world beset by stagflation, Jokowism has become a point of keen interest for the economic commentariat.

Even a cursory glance at his record since 2014 demonstrates a pragmatic but populist economic policy that favors state guidance over privatization and liberalization.

The prominence of Indonesia’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) epitomizes this approach. They have consistently served as the driving force behind infrastructure development and other social welfare initiatives – and that is by design.

As international economist Kyunghoon Kim argued in a recent paper, Jokowi and his SOE Minister Erick Thohir have been deliberate in shifting the focus of state enterprises from profit generation to domestic development in sectors such as banking, mining, and construction. Thohir was cherry-picked for the ministry in 2019, after having run Jokowi’s successful reelection campaign, and Kim notes how he has leveraged his private sector expertise to ensure that foreign investment falls into line with the national interest.

Putting Indonesia first is also at the heart of Jokowi’s downstreaming policy, a post-2018 innovation under which the country’s significant natural resources are manufactured into products at home rather than exported abroad as raw materials.

The government-owned Indonesia Battery Cooperation, for example, combines mining, smelting, and production capabilities, delivering high-value finished products to international markets, on top of supplying Indonesian nickel to a handful of distributors. This has helped the country to gain a foothold in the lucrative and booming electric vehicle (EV) market, and its benefits are being applied to other industries, from energy to consumer goods.

And while “resource nationalism” may go against the Western neoliberal consensus, Indonesia’s mineral wealth gives it the power to dictate terms to the benefit of government revenues, and to newly upskilled workers in the form of higher wages.

Jokowism, therefore, is deliberately populist yet pragmatic and even committed free traders have admitted its success.

However, with elections on the horizon in February 2024 and the Indonesian leader reaching the end of his two-term limit, there are questions as to how long it will remain the status quo. Given that Jokowi remains the country’s most popular politician – and may do so for some time yet – his successor is likely to want to pick up his economic legacy.

The ruling PDI-P party’s presidential nominee, Ganjar Pranowo, and Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto (who is also chairman of the Gerindra Party) are the two frontrunners to replace Jokowi. Neither has indicated a change in approach to Indonesia’s economy.

To the contrary, both men have benefitted from aligning closely with the president, Ganjar as a fellow PDI-P man and Prabowo as a foe-turned-friend, having lost to Jokowi in 2014 and 2019 but serving loyally in his cabinet since then.

If Ganjar and Prabowo are neck and neck in the race to win Jokowi’s endorsement, then their choice of running mates could prove crucial.

In terms of signifying their commitment to the president’s economic philosophy, Economy Minister Airlangga Hartarto is thought to be a shrewd VP pick, as is the aforementioned SOE boss, Erick Thohir.

Hartarto, as chairman of the Golkar Party , is fairly well positioned in Prabowo’s “Grand Alliance,” while Thohir is polling strongly as a running mate for both Prabowo and Ganjar.

Speaker of Indonesia’s House of Representatives Puan Maharani has also been touted for the Ganjar ticket. Her legislative nous and political capital – Puan is the eldest daughter of PDI-P leader Megawati Sukarnoputri – would certainly be of value in executing on the economy.

The tickets are clearly still in flux and running mates likely won’t be chosen until October. That said, there is little doubt that economic issues such as consumer prices and employment will dominate Indonesia’s 2024 elections.

No candidate is going to break comprehensively with the past nine years of policy under Jokowi – the political and economic risk is simply too high. Instead, they will surely be focused on building a team that can take up the mantle of Jokowism in his absence.

And because Indonesians won’t settle for the same for long, any viable ticket will need to have the ideas and experience to take the country forwards – and to do so in an era of even greater economic and geopolitical upheaval than was experienced in Jokowi’s tenure.

Will Jokowi’s Economic Legacy Survive Beyond Indonesia’s Election?

Source: Frappler

0 Comments